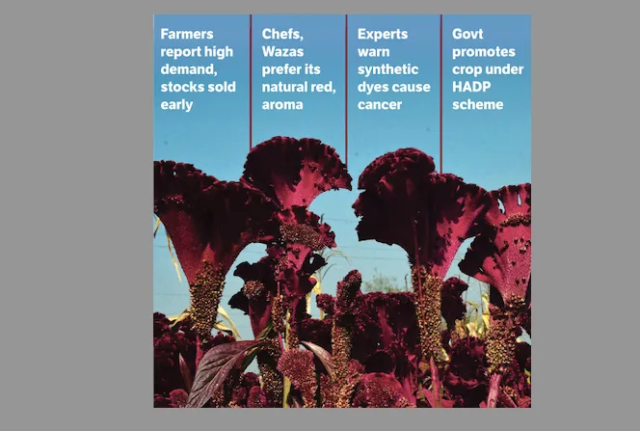

Srinagar, Oct 26: Amid growing concern over the use of synthetic and carcinogenic colouring agents in Kashmir’s traditional cuisine, a crimson flower once forgotten is reclaiming its place on the platter and in the fields.

The Kashmiri cockscomb, locally known as Mawal, has staged a remarkable comeback as people turn to natural food colourants, reviving an ingredient and an entire cultural legacy.

The revival comes at a time when the Valley’s food safety debate has intensified following the recent “rotten mutton” scandal, which exposed loopholes in meat hygiene and the rampant use of artificial colours to enhance the appearance of dishes served at weddings and restaurants.

As public awareness grows, many chefs and consumers are rediscovering Mawal – the deep red, velvety flower of Celosia cristata – as a safe, traditional alternative that has been part of Kashmiri culinary heritage for centuries.

Noor Muhammad, a farmer from Srinagar’s Rathpora area, points to rows of crimson blooms drying in the autumn sun.

“I have 3 kanal of land under Mawal cultivation,” he says proudly. “I’ve been growing it for 15 years, but there was a time when people had completely forgotten it. Chefs and restaurants were using synthetic colouring powders instead because they were cheaper and easily available. Now, with awareness about the diseases caused by these harmful chemicals, people have started demanding the real thing again. This year, my entire stock was booked before harvest.”

Another farmer, Muhammad Jabar from Chadoora, explains that Mawal requires careful timing during harvest.

“We pluck the flowers in October,” he says, gently rubbing the dried petals between his fingers. “If we delay till November, the colour loses its intensity. After drying, the petals are ground into fine flakes. When soaked or boiled, they release a rich red pigment that gives the Wazwan its authentic colour. Apart from its natural hue, ‘Mawal’ helps digestion and is light on the stomach – something no chemical can offer.”

Cooks and traditional Wazas (master chefs) across the Valley echo this sentiment.

In Srinagar’s old city, master chef Ghulam Hassan Waza recalls how his father and grandfather never cooked Rogan Josh or Rista without Mawal water.

“Those days, we didn’t have these chemical colour powders. The Mawal infusion gave a natural glow and depth to the dish,” he says, stirring a pot in his small kitchen. “Later, everyone started using artificial colour to make dishes look redder. It was quick and cheap, but now people are realising it wasn’t good for their health. Today, customers themselves ask for Mawal-based dishes. They say the food tastes better and feels lighter.”

At a popular catering unit in Hyderpora, chef Bilal Ahmad agrees.

“When we prepare wedding wazwans, the difference is obvious. Mawal gives an earthy aroma, a deep red shade, and a gentle flavour. The synthetic colours just stain the oil and meat – there’s no soul in it,” he says. “Now, people want traditional taste and safety. Even guests notice the difference.”

Food technologists and health experts see this shift as a positive outcome of growing awareness. Dr Showkat Ahmad says many of the artificial colourants used in local food are industrial-grade chemicals unfit for human consumption.

“Synthetic dyes like Sudan Red are known carcinogens and can damage the liver and kidneys when consumed over time,” he said. “Mawal is a completely natural product. It contains antioxidants, has mild anti-inflammatory properties, and acts as a digestive aid. It’s not just about colour. It’s about bringing health back to the plate.”

The rising demand has also caught the attention of policymakers.

Under the Holistic Agriculture Development Plan (HADP), the Department of Agriculture, Kashmir, is encouraging farmers to take up Mawal cultivation by distributing saplings and providing technical support.

Officials describe it as a low-maintenance, high-value crop that thrives in Kashmir’s summer climate.

In late 2023, Kashmir exported its first 120 kg of dried Mawal to the United States, a milestone that opened the door for further international trade in natural colourants and herbal ingredients.

“This flower has the potential to become a part of Kashmir’s niche export basket, along with saffron and lavender,” says an agriculture department official. “There’s growing demand from organic and eco-friendly markets abroad. It also supports rural livelihoods, especially for small farmers and women growers.”

Beyond economics, Mawal carries deep cultural and medicinal significance.

The flower, which resembles a rooster’s comb, has been used in Kashmiri households for generations.

Traditionally, families would dry the blossoms in sunlight and store them in jars for year-round use.

Elders often brewed Mawal tea or added it to gravies not only for its colour but for its believed healing properties. Folk healers used it to cool the body, improve blood circulation, and ease digestive discomfort.

For many Kashmiris, returning to Mawal is about reconnecting with their roots and rejecting artificial additives that crept into their kitchens over time.

Fatima Begum, a homemaker from Srinagar’s Nowshera area, recalls how her grandmother always used Mawal for festive cooking.

“She used to say that nature has everything we need,” she says. “For years, we ignored that wisdom and ran after shortcuts. Now, we are going back to what is pure and healthy.”